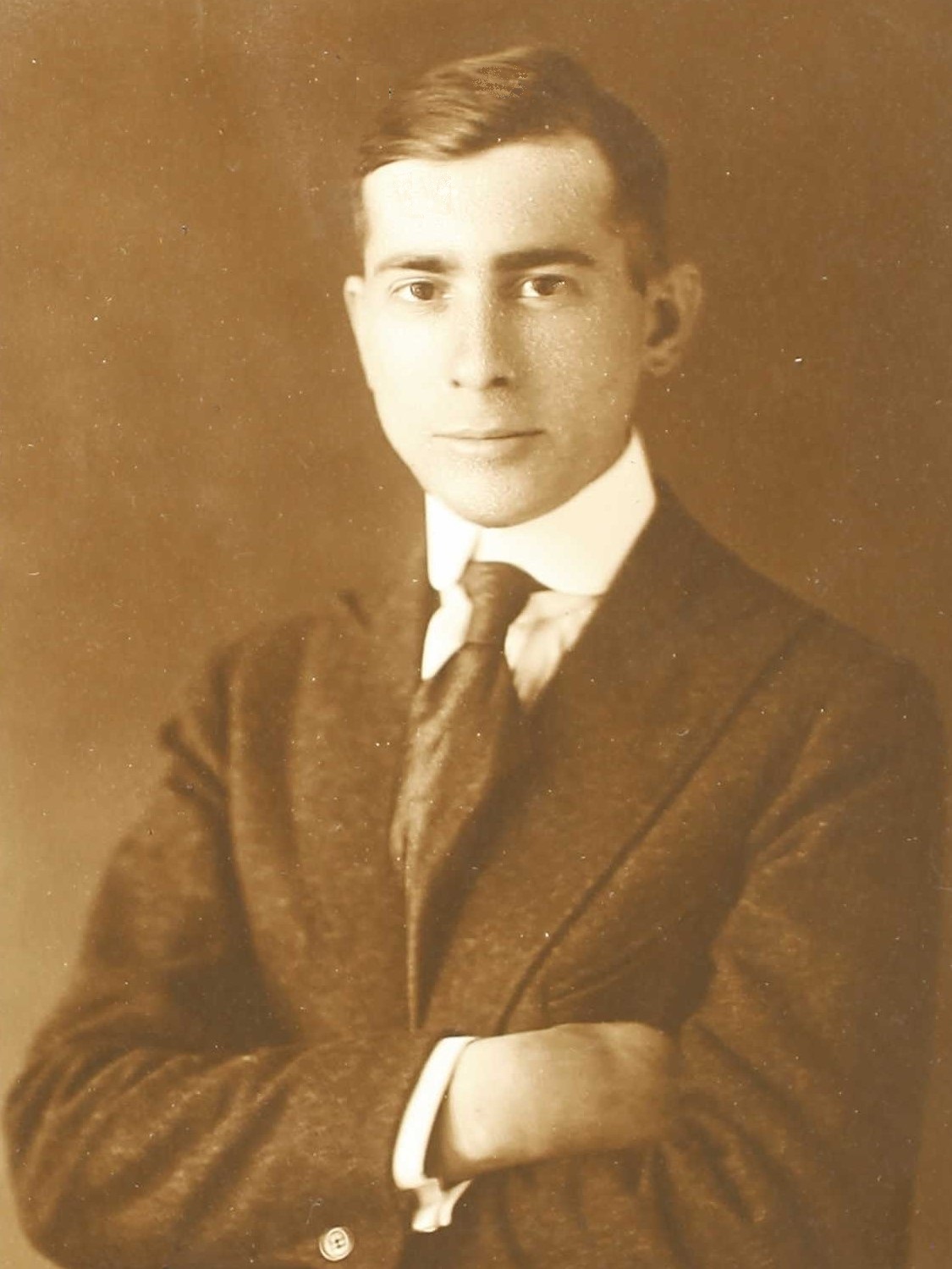

Private Joseph P. Devir

WAR LETTERS from contestants in The Record Prize Competition. "An Air Battle" by Private Joseph P. Devir, "Frenchman falling from burning machine still game."

On the morning of November 3, 1918, the first platoon of Company A, 313th machine gun battalion, of the 80th Division was given orders by the commanding officer Walter C. Lunden, to pass through Buzancy, which the night before had been under heavy shellfire and which during that period several casualties were encountered by our second platoon. Passing through Buzancy, which was almost shot to smithereens by the Hun artillery, we traveled zigzag over that section in pursuit of the Germans. Late in the afternoon after our second platoon had covered many kilometers, lugging along its quota of Browning machine guns, tripod, water can, condensing tube, boxes of ammunition, picks, shovels, etc., our progress was halted by bullets from a German machine gun sniper. At that time we were between a strip of wood, which the day before was in possession of the enemy. The swish zip swish noise made us take to cover. At that time we were between Buzancy and Vaux. Ahead lay Sommauthe. After a little while, “up and at ‘em“ was the order. Soon we were on the side of a beautiful valley. We halted for a rest; also, for orders.

While lying there, swarms of airplanes flew over our heads toward the German lines. About 150 machines of various Allied makes and designs were in the fleet. Twenty minutes later they came back, probably bombing and scouting planes fulfilling their mission of dropping their ammunition and taking troop movement pictures. It was a treat to see those air fighters, all playing the game for our cause.

While lying there, swarms of airplanes flew over our heads toward the German lines. About 150 machines of various Allied makes and designs were in the fleet. Twenty minutes later they came back, probably bombing and scouting planes fulfilling their mission of dropping their ammunition and taking troop movement pictures. It was a treat to see those air fighters, all playing the game for our cause.

Not long after that scene, several machines appeared in view and someone yelled: “There’s a fight. Look!” Sure enough, it was. Ten airplanes were heading toward us, seven German planes and three Frenches, it was later learned. Bing! Zip, Zip! All ten were cutting loose their machine-gun fire. Some fellow in our platoon cried out: “Down or you’ll get hit!“ Several boys dropped to the ground, but more than that didn’t - they wanted to see a real air battle. In fact, they did. I’d say a very sensational one.

Whiz! Whiz!! flew a bunch of machines above us, raising hell in the air with the crackling and barking of their weapons. Two more planes were 50 yards behind. Here develop a real battle between the Frenchman and a Hun aviator. Around the pair of rival sky-warriors flew. Up, then down, sideways, upside-down and otherwise they maneuvered, sometimes barely off the ground five feet. The French aviator tried to dip under the Hunman to get into position, where he could use his machine-gun effectively, but the German outguessed the Frenchie at this stage and cut loose his automatic machine gun, which set fire to the Allied man’s machine.

The French pilot, game as they make ‘em, dodged and shifted his aircraft around and tried to get back at his enemy, but failed. More bursts of bullets sang from the Hun’s gun and the Allied aviator, seeing his plane was going wrong, manages to turn the machine and makes for a landing across the valley. 150 yards from bank to bank. Just as the Frenchie was halfway across the valley, some 200 feet deep, the nose of his machine tilted downward. By a miracle, his plane went all the way over and hit the top of the opposite bank and turned a complete somersault. The compact threw the Frenchman out of his strapped seat headfirst to the ground. Ten feet above the Jerry was in pursuit, cutting loose with his tracer or blazing like bullets to make sure of his game.

This incident is another illustration of the way the Huns fought. Ordinarily, in aviation, I believe, when you down the enemy machine ablaze, it’s a victory, but this German airman’s view was apparently different.

After hitting the ground hard, the Frenchie managed to run or fall down the side of the hill of the valley about 10 feet in his endeavors to get away from the bullets of his rival.

I, being a spectator to this and seeing the Frenchie across the valley with his clothes ablaze, caused me to run over to where he laid and give first aid. Another fellow from our platoon, Private Albert Easha, of Pittsburgh, also followed my actions. When I got to the Frenchie, his clothes were still burning. He was in great distress, but conscious and directed Easha and myself how to take his aviator’s suit off. When we freed this from his body we saw that he had a hole in his left thigh about the size of an ordinary man‘s hand, where the German’s burning tracer bullet pumped him. Below it was another hole, where two bullets had also hit. After bandaging his wounds the best we could, two infantrymen came along with a stretcher, and Easha, the two doughboys and myself carried him back over a kilometer (1100 yards) to a first-aid station which was just being opened up.

While giving first aid to this French aviator, I thought I was due myself for a trip to a hospital, for German machine gun fire swept over our heads while we were outstretched on the side of the valley. Zip, zip, swish! they went. We weren’t far from the Huns then, as the valley apparently was under observation. My steel helmet, which I was wearing at the time, I put over that wounded aviator’s head for my sympathies were with him. After laying there for about 10 minutes we crept along the side of the hill to a place where we could get the Frenchie out of range of those tantalizing lead pills. All this Frenchie would say during this time was, “Ou, La, La!”

“Game as they make ‘em” was this French aviator, who told me back at the first-aid station that he was ranked only as a sergeant.

Private Joseph P. Devir

Company A, 313th Machine Gun Battalion

80th Division

SOURCE: www.phmc.pa.gov/Archives

Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948

Published on Ancestry.com, 2015, Provo, UT