Bernard Lipscomb Jarman

The fighting in the open battlefields during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive subjected the advancing American soldier to a volley of enemy machine gun fire, gas attacks, and a barrage of artillery and mortar rounds raining down upon them. The soldiers would try to get as low as possible in order to protect themselves from being totally exposed. This sometimes required occupying the slump of earth created from a newly formed shell hole.

This was the scene in Nantillois, France on October 4, 1918, as a young medical officer from the 313th Machine Gun Battalion recalled in a letter that he wrote to his father: “We were at the war front and first my dentist was injured by being shot through the knee. I fixed him up and then I stooped down in a shallow trench partly filled with water contaminated with mustard gas, an enlisted man was on each side of me. A little post was on the edge of this trench for telephone wires. At first, I got behind it, but for some reason that I will never know, I moved up just a foot. Then the man below me moved up to where I had been, thus we three were also close together that we just about touched. Then a shell hit about 2 feet from us making a large hole and fragments of steel scattered in every direction when the shell exploded. The man behind the post, partly protected as he thought, was instantly killed. Had I not moved up I guess this fate would have been my fate, it was just that distance, of less than 2 feet, which has me here today.”

That medical officer was First Lieutenant Bernard L. Jarman who recalled that day in October to his father some thirty years later as being “one of the most trying days that my young life had to that time experienced.“

Bois des Ogons located north of Nantillois from the Griffin Group photos purchased through Meuse-Argone.com

Jarman was born in Charlottesville, Virginia and graduated from the University Of Virginia School Of Medicine in 1915. He interned at Gorgas Hospital, a U.S. Army hospital in Panama City, Panama, (originally called Ancon Hospital), and interned at the Touro Infirmary in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1917, Jarman was commissioned a Second Lieutenant with the US Army Medical Corps and attached to the 313th Machine Gun Battalion, 80th Division.

After returning from the Great War, Dr. Jarman continued his postgraduate training in Washington DC and was certified by the American Board of Otolaryngology (ear, nose, throat specialty). He also finished postgraduate work at the Army Medical School in Washington DC, and completed Flight Surgeon School at Mitchel Field, Long Island, NY, in January 1922. By June 1922, Jarman had obtained the rank of Captain and was assigned by the Medical Corps to a hospital in Boston, MA. By September he was sent to Camp Devens, MA, to finish out his commission in the Army. Ironically, Camp Devens was the same camp that processed the final discharge of many of the men in his machine gun battalion just three years earlier when they returned from the war.

In 1926, the Air Commerce Act was passed by Congress charging the Secretary of Commerce with the development of air commerce, issuing and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, certifying aircraft, establishing airways, and operating and maintaining aids to air navigation. In 1927, Dr. Bernard L. Jarman became the first medical examiner for the Civil Aeronautics Agency (the CAA later became the Federal Aviation Administration in 1958). Dr. Jarman was a charter member of the Aero Medical Association (aka Aerospace Medical Association) and was the Aero Medical Association President in 1937-1938.

In 1926, the Air Commerce Act was passed by Congress charging the Secretary of Commerce with the development of air commerce, issuing and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, certifying aircraft, establishing airways, and operating and maintaining aids to air navigation. In 1927, Dr. Bernard L. Jarman became the first medical examiner for the Civil Aeronautics Agency (the CAA later became the Federal Aviation Administration in 1958). Dr. Jarman was a charter member of the Aero Medical Association (aka Aerospace Medical Association) and was the Aero Medical Association President in 1937-1938.

When the United States entered into World War II, Dr. Jarman served as a Flight Surgeon at the Bolling Field Air Base in Washington, DC, an installation that served as a training and organizational base for personnel and units going overseas. As a military medical officer, or flight surgeon, he was tasked with adhering to a strict set of medical standards to ensure the health and safety of his pilots, and ultimately, the personnel who would support these aviators. He retired from the military in 1949 with the rank of Colonel.

Dr. Jarman maintained a private practice in Washington DC at 1028 Connecticut Avenue, as well as in his home at 4929 Tilden Street, where he lived with his wife Rose Pollio Jarman until his death in 1962.

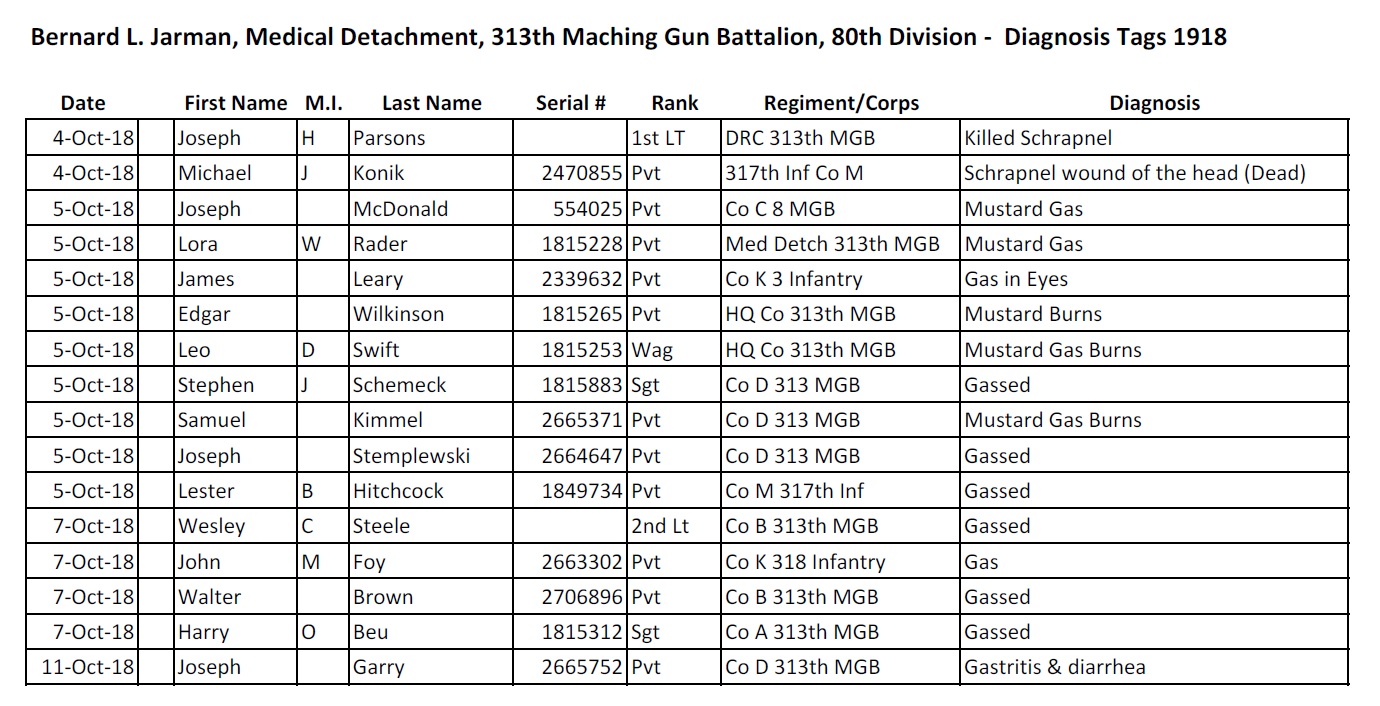

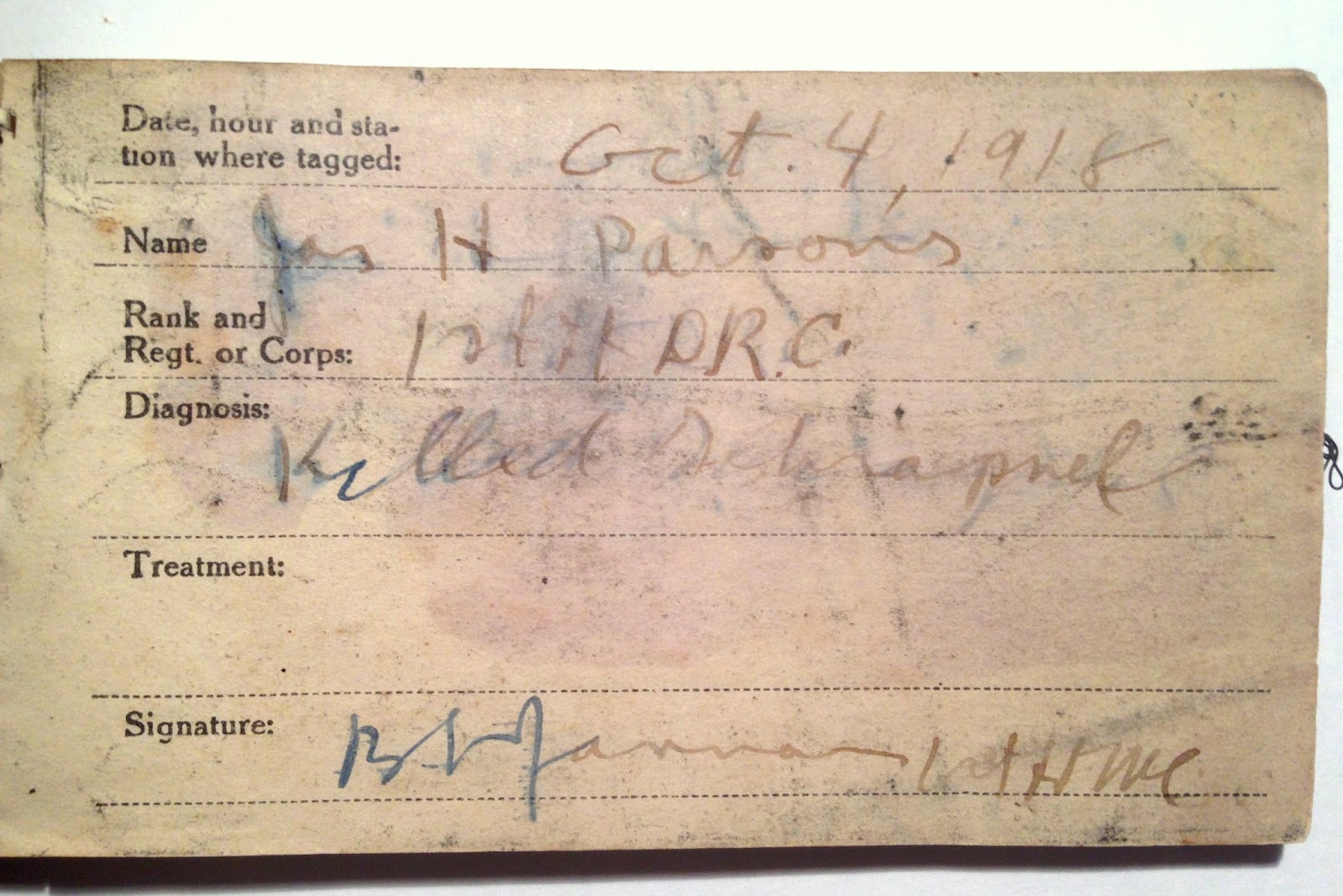

Medical Tag Book entry for the dentist Jarman mentioned, Joseph Harold Parsons, killed by shrapnel, October 4, 1918.

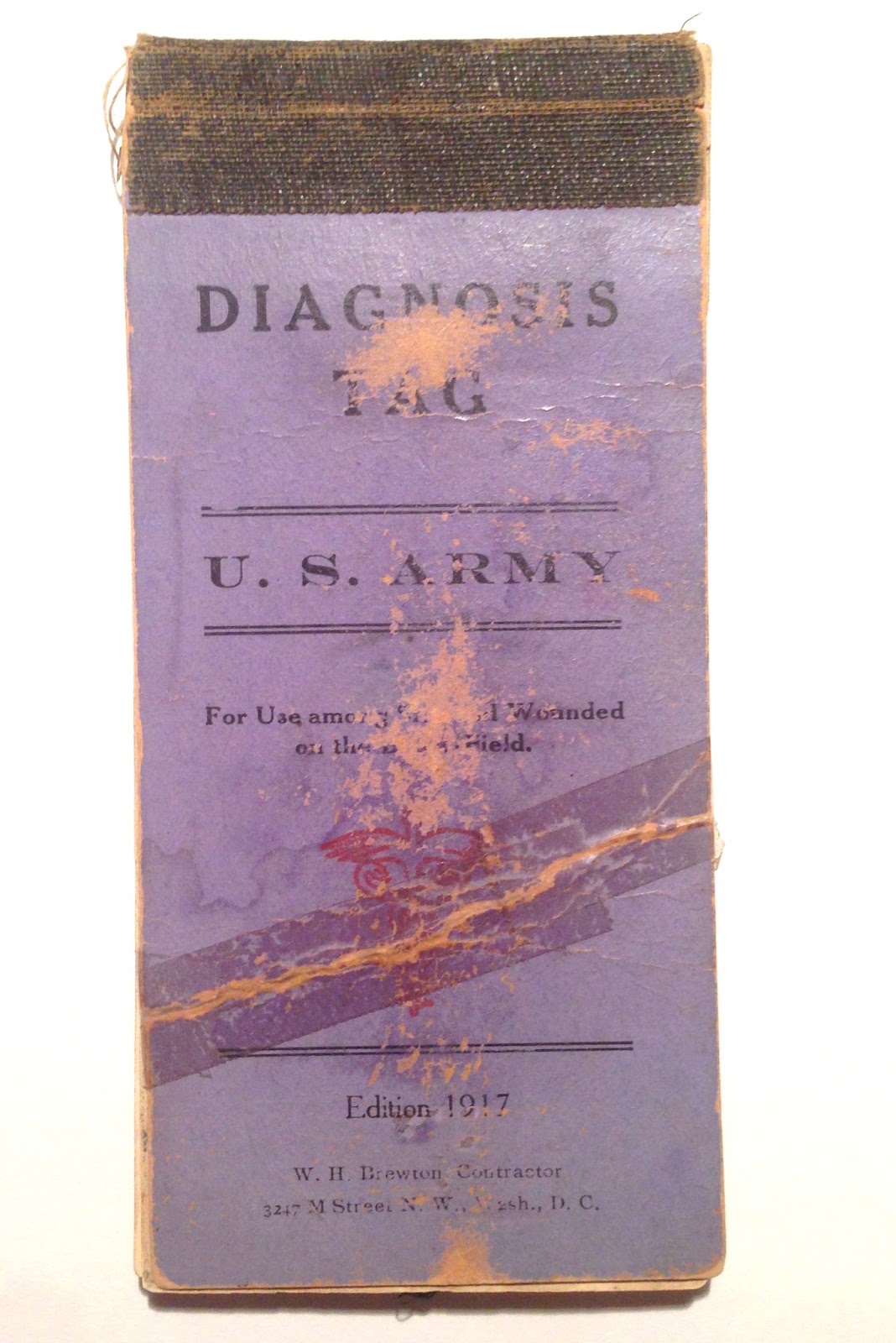

Jarman’s entire letter to his father has been recorded in my book “Good War, Great Men.” One of the items that he recalls in his letter was the use of a “Medical Diagnosis Tag book” where he recorded a soldier’s name, unit, and medical condition. A soldier would have been tagged with a piece of linen paper, and a carbon copy of the details were retained in the medical tag book. Jarman’s medical tag book was actually given to me by his great nephew, John Armstrong, during my research of the battalion. I was honored to have received this battlefield relic, and appreciating the need to preserve this history, I donated Jarman’s medical tag book to the Erie County Historical Society in Erie, PA. Many of the men recorded in this book came from that region. I was also fortunate to have been able to show these first-hand recording, taken during the battle, with at least three descendants of the men listed in that book who were either killed or wounded.

1st Lt Bernard Jarman's Medical Diagnosis Tag Book now at the Erie County Historical Society